From Dunhill to Ferndown: An Interview with Les Wood

Leslie Wood is one of the towering figures of post-war English pipe-making. As a silversmith, he has left his mark—if you’ll excuse the pun—on countless pipes from countless makes. Together with his wife Dolly Wood, he crafted handmade pipes that are widely considered to be some of the finest smoking instruments ever made, doing so for over three decades until the two retired in 2016. Mr Wood was kind enough to sit down with James from MBSD Pipes and discuss some of the lesser-known parts of his five decade career in pipes. The following has been compiled and condensed from several interviews and follow-ups conducted over the last few months.

If you are interested in the selection of Les and Dolly’s pipes that MBSD currently has in stock, please you can find them under the Ferndown tag, or by clicking here. If you would like to know more about upcoming Ferndown and L&JS listings, including our remaining new old stock Jacobean pipes, feel free to contact us using the form on the MBSD homepage.

I thought we’d start with a basic timeline of your career, then we can use that as a jumping off point for more general questions regarding your work. Does that sound good?

Yes, no problem.

Great. So, as far as I understand, you started at Dunhill in 1963, is that correct?

Yep. Two weeks after my birthday.

What birthday was that?

My 15th.

Things were a bit different back then, I take it?[1]

Yeah. No college, no nothing. You didn’t even get an exam at our school. At that particular time, there was a service in the education authority over here called the Youth Employment Service.[2] They’d come to the school and they’d interview you, and say, “What are you good at?” Well, the only thing I was good at was my hands.

The rest of the education was useless to me because my brain didn’t absorb nothing. But I had two very clever hands and they said to me, “We have a position open here at Alfred Dunhill for silver mounting.” But I hadn’t got a clue what that was. Never heard of it. So, they arranged an interview and I went along there started at Dunhill’s two weeks after I officially left school.

So, you worked for Dunhill for 19 years—that’s what I have here—is that right?

Yeah, it’s 18 or 19. I think it was coming to the end of the 18th year when me and them parted company, let’s say. Dunhill’s gave us a contract to leave. That was part of the deal for me to go, to give me a contract for one year of work so that I could establish myself and carry on for whatever the next amount of years was until I was 60.[3]

What year was it that you went independent? Just so I have the record straight.

That had to be around about ’78/’79. That’s when L&JS Silverware was founded. When I left Dunhill’s, Jimmy Craig[4] came with me. Robert Morris as well, and two other fellows that I can’t recall the names of because they only stayed with us for a short time.

We had a workshop on Carpenter’s Road in Stratford, where the Olympic stadium is now.[5] Jimmy Craig, as you know, now runs and owns Ashton Pipes. That’s officially the “L&J.” It was “Leslie & Jim Silverware.”

That’s something I didn’t know.

It was very convenient, because when Jim went his own way, my second name is John. So, it became “Leslie John Silverware.” Jimmy went his own way. He had other things that he wanted to do, and then Billy Taylor got in touch with him because I was up to my eyes in work. I couldn’t always do Billy’s silver and gold work for him. He got in touch with Jimmy, and him and Jimmy struck a bargain.

Oh yeah, Taylor also came out of Dunhill, didn’t he? I wondered if you had known each other there.

Yep. Billy came out of Dunhill’s a bit after me. I let Billy have his workshop at my place on Carpenter’s Road and he stayed there for one year with Frank Lincoln and Bernie Knighton. They all made [Ashton’s] pipes. Then, Billy wanted his own place, a space of his own. So, he bought a place in Romford.

Just to get the timeline right, of those 19 years you worked with Dunhill, were a few of them spent sort of half-in, half-out due to it later going through your own silverware business?

Yeah, that’s right. One foot in, one foot out.

That would bring us to around about 1982.

Yeah. We were doing lots of silver mountings for other companies in that time, actually. Dunhill’s would send us boxes of pipes to do, and lots of others would as well. Oppenheimer,[6] James Upshall, Barling […] I think the only company we didn’t do anything for was Peterson’s.

Sounds like a lot of work.

Yeah, it was once everybody knew that I’d left Dunhill’s. One of the reasons I fell out with Dunhill’s was because they owned Charatan.[7] Now, Charatan wanted me to do silver mounting for them. And the [Dunhill] management at the time said “No.” They weren’t prepared to have Charatan pipes mounted, so the managing director of Charatan, Dennis Marshall, got in touch with me privately and he said, “Would you do some for us?” I said, yeah, I don’t see nothing wrong in that. It’s my workshop—I’ve got a private workshop in my house. But once Dunhill found that out, they gave me an ultimatum: “Stop doing Charatan’s silverwork or you’re history.” And I’m afraid that’s not the right thing to say to me [laughs], because I was history within a week.

Were you making your own pipes by this point? And had “Ferndown” come about in any shape or form yet?

We started making pipes before we stopped doing work for Dunhill’s. From ‘78 onwards was when we concentrated solely on the silverwork. Around ’81- ’82, we started to do the “L&JS Briars.” L&JS Briars had numerous names. One was called—I’m trying to remember now, as we’re going back a few years. There was “Tudor”; “Elizabethan” was another; “Jacobean” was one too.[8] The Jacobean never lasted because the Americans couldn’t say it [laughs]. They all called it by different versions of the word. “Jacobian,” “Jacobeen”—it got called so many different names.[9] We carried on with Tudor and we carried on with a couple of others. That’s where we introduced “Ferndown.” So, there was a Ferndown, “Root,” Ferndown “Tudor Root,” which was a dark [stain], Ferndown “Reo,” which was in red, Ferndown “Bark,” and a Ferndown “Tan.” We only made five colours as such.[10]

I noticed on some of the Jacobean pipes that they had different finish names to the ones used for Ferndown. The light-stained one seems to have been called the “Natural” at one point. Was this to avoid legal troubles with Dunhill, given “Root” is similar to “Root Briar”?

That’s how it started. Then I went to Dunhill’s and said I wanted to use “Root” and asked if they had any problem with that, as I worked for them. They said, “No, stamp them what you want.”

I see now. So, what’s the difference between a Jacobean and a Ferndown?

They [the Jacobeans] were really the first part of our production in the early days. They were all hand turned and [oil] cured like the Ferndowns, but they had a cast mouthpiece, whereas the Ferndowns all had hand cut ones. [For the Jacobeans] we got involved with a distributor—one in England and one in America—and they wanted everything cheap. And that means we were working, you know, 11 hours, 12 hours a day producing something with no profitability to it.

That sounds far from ideal.

Put it this way: I knew we could do better. We needed to up the market. We said, “Look, this this can’t go on. What we’re gonna do, is we’re going to buy the briar blocks ourselves and we’re going to turn a completely new range called ‘Ferndown.’” That was around ’83. I knew a very talented cabinet maker who made humidors, and I told him that we were going to create a range of completely handmade pipes, and I said to him that we were in two minds as to what to call it. He said, “Well, why don’t you call it after your house?” Because “Ferndown” is the name of the house where I live. So that’s what we’ve done, and it just carried on from there.

We decided to rent part of a workshop in a village called Clavering. I knew the fella who owned it from buying all the boxwood that we use for turning the silver (that’s what we turned it on because it doesn’t compress in any way). He had his own factory at Clavering, and he said, “You’re perfectly welcome to use part of my factory. Then came a very bad incident. He came in one day and he said to me, while I was sandblasting, says, “I’ve got a very strange feeling in my stomach, it just keep expanding.” I said “I don’t like the sound of this. This needs to be looked at by a doctor.” He said, “I saw a doctor the other day, he checked me out and said I was perfectly OK.”

He walked up to Dolly while she was making a cup of tea, and he just bent over and that was it. He landed on top of her. We kept the oxygen rate going—in other words, we performed CPR for the duration it took for the ambulance to get there—but the ambulance, when they got there, pronounced him dead on the spot. There was nothing they could do. So, we decided that the factory wasn’t the place for us to stay. We brought the workshop to the side of the house.

That’s terrible. I hope things were more smooth sailing after that. Did it take long for the new Ferndown make to take off?

In England, I’d already been selling Ferndown through two or three different outlets, James Barber being the biggest one. When Eddie Kolpin[11] got involved, we went to the RTDA[12] show in Chicago and we had all the stands set up. And people came in and they didn’t know me from Adam.[13] Eddie introduced me to all the different retailers, and it always the same question, “What’s the story behind the Ferndown?” And I’d tell them, and it basically took off from there. We went to about seven or eight of the RTDA shows. We were making for Eddie, at our peak time, probably 500 pieces a year. Then Ken McUmbrow[14] took it over before then because Eddie became seriously ill. And because of the way Ken sold, being out on the road continuously, production went up to about 7-800 a year. We worked seven days a week most years. And we did that for a long time. We would want to get to the workshop by at least 7:30 in the morning. And we would stay there until 7:00 at night. And that went on for a good few years, because they wanted the work, and I wasn’t prepared to subcontract it out to anybody. Because, once you’ve done that, you lost the ability to say, “That was my work.” And I couldn’t do that. It had to be mine and Dolly’s work.

The RTDA shows, those will have been what, 1980s?

Yeah, in the 80s. We went to Chicago, Kansas City—I never went to the Las Vegas one, that was the only one I never went to. But what we’d done is fly from England to Topeka, Kansas City, where we’d see a fella who had a business down there, retailing pipes. We used to have a week down there in a hotel where we’d go fishing and clay pigeon shooting. Then we would fly up to wherever the show was going to be, and we would stay there for four or five days, and then fly home. Can’t fault it. We’ve thoroughly enjoyed ourselves all the years we used to go out there. Even the AITS[15] shows in England. When you go back to the early AITS shows, it was always in Solihull. And at nighttime, after you’d closed the stand, we all accumulated in the bar. The managing director of Peterson pipes—I can’t remember his name—was an Irish gentleman that would spend all night long singing little Irish songs. We’ve had some fantastic times as pipe makers.

Now that you’ve mentioned James Barber, I wondered if you could tell me a little more about your working relationship with the companies you made pipes for. I’m familiar with the James Barber “Chevin,” and I know there was also Astleys and Dan Pipe. Would you be able to speak more on that?

Yep. What I used to do with Paul [Bentley, Astleys owner] is he’d ring me up and say, “What have you got?” And I’d say, “Well, I’ve got 30 pipes going through at the moment.” And I used to take them up there [to Jermyn Street] and he’d go through them. He’d go, “Can I have all these ones? Can you take them back and make them Astleys?” And that’s what I used to do. But in effect, they would just be Ferndowns.

With the James Barber’s pipes, he [Barber] wanted something that he could promote his name with. He wanted the names to represent certain parts in Yorkshire. And I said, “Yeah, no problem. You tell me what you want. I’ll make them. And if you want to tell people that I made them, no problem at all. Or you can just say ‘I’ve had them made,’ I have no problem with that.” I don’t get involved in that side of it. We made quite a few over the years, but I can’t remember the names now, but they were all named after parts of Yorkshire.[16]

What about Dan Pipe and the Elwood make? I think that’s one of the stranger Ferndown stories I’ve heard about.

Yeah.

Could you take me through it?

You gotta go back… oh, 25 years? Holger was the one that dealt with most of that—Holger Frickert.[17] The man who owned them [Dan Pipe][18] only had a limited amount of English, so everything was done through Holger. Lovely man. I still talk to him on the phone all the time.

By then I was going out there and doing demonstrations of silver mountings for Dan Pipe. I didn’t quite understand this, but because of the German language, they couldn’t use the word “Ferndown.” Holger said to me one day, “We can’t pronounce this, we’ll need another name.” I said, “What do you want to do then?” It was Dan Pipe that said, “Well, we’ll call it ‘Ellwood’”—E-L-L-W-O-O-D—“because ‘L. Wood’ stands for ‘Leslie Wood.’” Unfortunately, they’d forgot there was already a cigar manufacturer in Germany, which has that registered as a name. I’d already had all the stamps made to say “Ellwood,” but luckily, when you stamped it, unless you actually looked it under a magnifying glass, it just looked like one “l”. So, we came to an agreement with the cigar manufacturer. The stamp remained the same and we carried on manufacturing “Elwood” pipes for them.

Did Elwood end around the same time as Ferndown?

I think we packed it in when I was about 62 or 63. The older you get, the less your ability to manufacture. It’s straightforward as that. You’re getting older. Yeah. And I knew the circumstances of the Dan Pipe factory and what was going on over there. That was slowly declining. And that was an opportunity to say to them, “Look, there’s no point in you doing all this photography and all this sales service on behalf of Elwood Pipes when you’re only selling maybe two or three a month. I’m quite happy if you want to withdraw it from the system.”

So, they withdrew it from the catalog. No problem to me at all. By then I was decreasing my production, and at the finish I stopped production for America as well. The only person I was making for at the end was James Barber.

As a quick aside, I know there are Elwood brand pipe tobaccos from Dan Tobacco—or there were, as I think the first one is discontinued. I’ve got a tin of Elwood Flake No. 2 here, actually. Were you involved much in that side of things?

No, I’ve let Holger do all the work on that. He came up with the blend. I know very little about the blending of tobacco. I went out there to the back when we were out there. We went down to the tobacco factory quite a few times and they showed me the different mixtures, and they said “Right, these are the ones we’ve made for you.” Smelled lovely. But that’s as far as my contact with the tobacco side of it goes. I’ve got three tins of it sitting in my cupboard in the display cabinet [Mr Wood reaches to his cabinet and retrieves a set of tobacco tins]. Oh, I’m gonna tell you what I’ve got. It’s not “Elwood,” it’s “Ferndown.”

Well, here’s me showing my ignorance, because I didn’t know there was a “Ferndown” tobacco too.

[At this point in the interview Mr Wood and myself spend a very uneventful few minutes going over the minutiae on our respective tins of Ferndown-affiliated tobacco.][19]

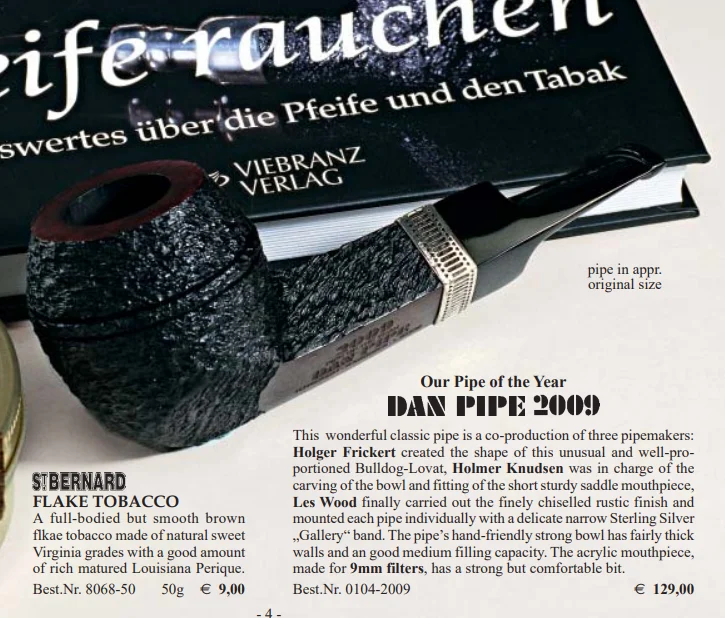

If we go back to the “slowing down” part from before, I wanted to ask, because I remember the Dan Pipe “Pipe of the Year” for 2009[20] that you worked on in collaboration with Holmer Knudsen and Holger Frickert.[21] Did the reduction in your output play a role in all three of you coming together to make that pipe?

Funnily enough, I was going through the stamps two days ago. I’ve got every stamp that we’ve ever made for every pipe, and I’ve found the Dan Pipe stamps for 2009. And there’s other year stamps on there as well. It was because, when they first started doing the pipe of the year, they were ordering in excess of 200 pieces of one shape. And I read things into conversations when I’m having them with people like that. Ordering 200 was now not the thing for them to do because all of their sales were reducing. But it wasn’t something they necessarily wanted to take up with me and say, “Oh, we don’t want those pipes anymore.” So, I automatically said to them, “You shouldn’t now buy 200. It’s silly because you’ll just end up sitting on the stock, which you don’t need to. There was a limited market within Germany, and very few of the Elwood pipes went to America, and none of them came to England at all because they had the Elwood stamp on them. The only ones that went to America were by mail order. So, as sales were decreasing—and as it was a time in my life where I was quite happy for that—it was time to say, “It’s been very nice working with you. I wish you all the best.”

Yeah, that sounds reasonable. I’m going to bring us back to the beginning again now, because there’s a couple of gaps that I wanted to fill in. The biggest one, for me, is the question of how you learned to make a pipe. Did you teach yourself? I know you learned silversmithing at Dunhill. Did they teach you to turn bowls and cut stems too?

Yep. The silver mountings department at Dunhills never runs full time. And I have to have things to do. Because I get bored. So, there was two or three other departments that I’d go to. Harry Sagot was in charge of manufacturing for all the fraising of the mouthpieces. Henry Law was in charge of fitting all the vulcanite. [The pipes] then went to the papering department, which was downstairs, on the middle floor of the factory. Then they went over to the finishing department, where Dolly worked. And because I wanted to, I was always getting involved. I couldn’t sit there and read the newspaper. So, I used to go into the other departments and say to them “Right, what can you teach me today?” The one thing I’ve got is 2 hands that do exactly what they’re supposed to do. They need to be shown once, and then I’m turning wood, I’m turning vulcanite, I’m fraising vulcanite, I’m pumicing vulcanite, I’m finishing the pipes. I’m going right through the whole of the system in the 19 years I was there. For the silversmithing part, whilst at Dunhills—because I always have to have my brain occupied—I went to Sir John Cass College[22] in London three nights a week for five years. That’s the principal silversmithing college in London, where all the big companies sent their apprentices to. I managed to get in there after lining up in the street for or seven or eight hours to get a place.

That was the other side of the trade, because in Dunhill’s, silver mountings was manufacturing silver mounting for pipes, whether it be cap bands, whether it be silver bands, or whatever. At college, I did the other side of it, which was manufacturing tea pots, coffee pots, or stuff which relates to genuine silversmithing. I used to leave Dunhill’s at 5:00 in the afternoon and catch the bus up to Gardener’s Corner, where the college was.

After that I went to another college and did a degree in engineering craft fabrication—again, manufacturing in metal, but this time manufacturing in steel. I took my City and Guilds[23] there and passed in the Distinctions.[24]

I’ve got another question that I’ve always wanted to ask. You came out of Dunhill originally, where you first learned to make pipes. But one of the iconic Ferndown finishes is the “Bark,” which is rusticated. Since Dunhill didn’t rusticate their pipes, I wondered how it came about that Ferndown did. Another question is how you arrived at that very distinct style of “Bark” rustication. What was the process behind all of this?

Are you familiar with Peter Wilson from Duncan Briars?[25]

Vaguely.

I got on very well with him. I always got on very well with all the manufacturing side, but I never got on very well with the management side of firms. But those people that knew the tools and could pick them up and work, they’re the ones I liked. I showed Peter one day as he was down at my workshop here. He said, “How are you rusticating your pipes?” I showed him how we’d done it and he went, “No, that’s the wrong way.” So, he showed me a different way and that’s the way we used from then on. The problem with Peter’s way is, if you made a mistake, you seriously hurt your finger.

“Barking” Pipes the Ferndown Way

At this point in the transcript, Mr Wood explained the technique involved in the “barking” of Ferndown pipes. As Mr Wood’s explanation used visual references, and due to my own endless confusion about the technique—which Mr Wood patiently remedied—I will instead provide a brief written summary of the process. These are not instructions to be followed, and if you do attempt to “bark” your pipes the way Les and Dolly did, MBSD is not responsible for any injuries or damages that may occur from doing so.

- Take a drill bit and a drill sharpener. Instead of sharpening the drill bit the typical way, by holding the sides of the point parallel to the sharpening wheel, press the point into the very edge of the wheel. This splits the point into two sharp points, essentially inverting the angle of its cutting edge.

- Mount the modified drill bit onto a fixed drill, lathe, or similar rotating device, and set it in motion. High speeds are required.

- Take a stummel and press it against the modified drill bit as it spins. This will rip off chunks of the wood. Hold the stummel tightly, taking care to prevent the force of the drill bit from pulling it out of your hands.

- Once you are satisfied with the “barked” stummel, switch out the drill bit for a wire brush to clean off any loose chunks of briar.

- Use a sanding tool to smooth off the tips of the “barked” briar.

Dolly does it brilliantly. I do it differently to her. I do it much heavier than her, but I think that’s simply because I hold it tighter than she does. Then she smooths off and highlights where you’ve chipped all that wood out, so that, when you get it in the right light, it’ll all glisten red, to a certain degree.

I’ve showed other people how to do it. I’ve never been averse to showing people how to do things. I’ve shown many other people how to make the drills, how to use them. Whether or not people use them is another thing, because they are dangerous. Because it’s got two points, and those two points want to run away from you all the time—it wants to climb up the drill as it’s going round—it doesn’t know the difference between your finger and that piece of wood. And it just rips through your finger. It happened quite a few times, I must say [laughs].

I guess that’s suffering for art, as they say. I do find it quite interesting regarding the Bark, because I struggle to think of a precursor, in England or abroad. It’s very different from, say, the “Irish” styles from Peterson and from the “Italian” styles from Castello or Savinelli. The closest I could think of was the micro-rustication you find in Danish pipes, like Peter Brakner or Bari, but even then, it’s not close at all.

It’s really because of the way we did it with the drill. The Italian version, originally—when Billy [Taylor] started going over to Italy to see Alberto Paronelli[26]—used spikes on the end of a tool, and they ripped the wood that way.[27] But we decided not to use that method. We used it for a little while, but there was no serious control over it as such. Then Peter showed me the way he did it, and I thought, “You’re onto a winner there, Pete.” I used to do a lot of stuff privately for him, which went in his name, and not my name. We carried on using his method, and it worked out perfectly for us.

I had another question that’s sort of related to that one, and to you and Dunhill. Apart from, say, their group 6, their Hand Turned, their Magnums, or other rare pipes, Dunhills are generally smaller pipes. Especially when you go down to the group 1s or 2s—but even their group 3s and 4s—they’re pretty small by today’s standards. On the other hand, Ferndowns tend to be quite big pipes, especially compared to Dunhill. Was there a conscious reason for this?

That’s right. The only reason was our view of it. We looked at them and went, “No, don’t like them. They’re too small.” They’re just as easy to make, we had no problem about turning them or anything else. But if I’m gonna stand there with a chisel in my hand, I don’t wanna produce something that big [Les gestures with his hands to indicate something very small]. I wanna see something at the end of it. I’ve got a pipe in [the other room]. Nobody’s ever seen this. I made this about 40 years ago. It’s a perfect straight grain. It runs from top to bottom, there’s not a flaw on it. That has been in my safe for about 40 years. It’s never been sold. It’s never been seen. You’re the first one to see it.

I’m honoured.

A couple of my friends have seen it who have got no interest in pipes whatsoever, and one of them, who does decorating for me, has this standard joke of “Have you written that pipe in your will for me?” Because he knows I’m not gonna sell it. It’s just there. Another one is the Dunhill “Aquarium” lighter.[28] Are you familiar with them?

Not personally, but I’ve seen pictures. I know they’re very expensive!

[Les gestures to a small, Dunhill Aquarium lighter] Well, there’s no reference on them that says so, but I made them from 1963 until I left. I didn’t do the painting, as that was always done externally. But I did all the panels and the fittings, with the last ones being made just before I came out of Dunhill’s. My decorator wants to take mine along to The Antiques Roadshow,[29] and he wants me to stand behind the expert and say, “What do you think about this?”

And he’ll go, “Oh, well this was made in 1952.”

And my decorator will go, “No it wasn’t.”

And he’ll go, “So, when was it made?”

And then my decorator will go, “Well, he made it in 1967.” [laughs]

I thought we might circle back to your working relationship with Mrs Wood. One of the things I find fascinating about Ferndown pipes is that they’re a partnership between the two of you. There have been plenty of pipe making factories and workshops where people are employed together and make pipes together but making something with someone you love is very rare, and not just in pipes. Are you able to say some things about that experience?

Well, we met at Dunhill’s. I’d been there about two years. Then, Dolly started working in the finishing department. And we’ve worked together ever since. And I think the fact we work together is that she doesn’t cross my side, and I certainly don’t cross hers. She decides if this or that pipe is suitable. I’ll make, let’s say, two dozen pipes. And I’ll give them over to her. I’ll pick the mouthpieces. I’ll fraise the mouthpieces out. Once I’ve got the mouthpieces filled out, ready for pumicing, I hand them over to her, and anything in there that she didn’t like, she would just give me back and go, “This one’s no good.” And there would be no discussion about it. She knows what she’s talking about. She would show me what she’s talking about, and I would go. “Yep, you’re absolutely right.” End of story. Then, she’s the one that decides the finish. If it’s gonna be a Bark, Root, Reo—she knows what’s gonna be best for the pipes.

I think that’s how it went on, because we worked back-to-back. Her side of the workshop is on the left-hand side, mine’s on the right-hand side. And occasionally she would let something go off the wheel and it would come straight over the top of my head, and I’d hear her laugh. She’d say, “Did it hit you?” And I’d go, “No.” And she’d go, “Oh, that’s a shame.” And we would laugh about it.

We married when we were 19, so we’ve known each other all that time. We were at Dunhill’s, then I came out of Dunhill’s while she was still there. She then left Dunhill’s because they wanted her to move to their other factory, and she didn’t want to go over. From then on, we’ve just made pipes together. There’s never been a problem. I do my part, she does hers. And I always say to people, the way she does it, it’s absolutely immaculate. That’s where the problem comes in [laughs]. Because I leave fingerprints on everything. I’d mount all the pipes up and I’d give them back to her and she’d go, “Oh. I’ve gotta refinish them all now.” “Sorry dear.”

It sounds a big part of it, then, is a good division of labour and a good sense of humour.

Oh yeah, yeah. The division of labour was definitely there because I know her finishing is far superior to mine. Even though she’s crippled up with arthritis now, she could probably still go in there and make a very nice pipe.

That’s sad to hear.

Well, both our hands are all twisted and bent now. And she puts that down to the finishing of the pipes, the way you have to hold them and turn them and. But you know, that’s just one of them situations that has occurred and we just put up with it.

If it’s any consolation, it sounds like you’ve had a tremendous career. People really love your pipes and, at the risk of sounding overly materialistic, they pay a lot of money for them, too, even on the pre-smoked estates market.

It’s given me a living and it’s given me a nice time. I’ve done everything I wanted to do. I’ve never been afraid to get involved. And people now send me messages online, saying, “Would you answer these questions? Would you tell me about this part?” Yeah, no problem at all. I’ve even had people down here and showing them how to do the silver mounting because they weren’t quite sure of why it should be done. I went to the factory at Charatan and showed Colin Fromm,[30] the fellow down there, where he was going wrong with all the silver mounting and showed him how to do the silver spigots. There was Northern Briars,[31] I made him [Ian Walker] a complete set of tools so that he could improve his silverwork, because I knew how he was doing it, but he just wasn’t doing it the way I do it. So, when he came down here for the day, he went, “Oh, I’ve realised where I’m not doing it exactly as you were doing it.” Ian’s a lovely fellow. I’ve known him for 35 years. And yeah, I share information with anybody. Because what have I got to lose? You know, there’s no point in me saying, “Ohh, can’t show you that. That’s a secret,” if someone says to me, “How do you do a silver band?” If you wanna get in your car and drive down here. I’ll show you how to do it. Simple as.

That’s lovely, and I think that’s a great place for us to end. Thank you again for this.

No problem at all.

[1] In England, children are required by law to attend school until the age of 18. In 1963, however, children were permitted to leave as early as their 15th birthday.

[2] The Youth Employment Service was a program organized by the British government to help school students find a suitable career path. This included training and placing school leavers.

[3] In another brief exchange, Mr Wood explained that Dunhill’s arrangement for him to work off-site as a contractor was in part due to a decline in the tobacco pipes market in the 1970s, which led to downsizing in Dunhill’s various departments.

[4] Jimmy Craig is currently the owner of Ashton, an English pipe company. Ashton was founded by William Taylor in 1983, with Craig later joining the company. After Taylor’s passing 2009, Craig took over the company and continued to manufacture Ashton pipes.

[5] A road in Stratford, East London. In 2012 it became part of the site for London’s hosting of the 2012 Summer Olympic Games.

[6] The Oppenheimer Group was a British company, most known in the pipe world for its ownership of various pipe brands. Around the time of Mr Wood’s involvement, Oppenheimer, through its subsidiary Cadogan Investments Ltd., had acquired and/or merged a large number of notable brands from England and France, including Comoy’s, GBD, Loewe & Co., Orlik, and BBB.

[7] Dunhill acquired Charatan in 1978, with manufacture continuing under Dunhill’s oversight until 1988. Charatan was then sold again, this time to James B. Russell Inc., in 1988. Dunhill re-acquired Charatan from James B. Russell in 2002. Dunhill continues to oversee the manufacture of Charatan pipes and tobaccos ongoing at the time of writing.

[8] Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean are all names for eras of the British monarchy.

[9] As far as European history and politics go, it would be very unfortunate to confuse Jacobeans, Jacobians, and Jacobins!

[10] Ferndown pipes were originally made in five finishes: Root (smooth, light brown/blonde), Tudor Root (smooth, brown), Reo (smooth, red brown), and Bark (rusticated, either in black with red highlights or tan).

[11] Edward Kolpin (Senior), founder of American tobacconist Tinder Box and, later, Ed’s Original Tinder Box.

[12] Retail Tobacco Dealers of America (RTDA), a trade organization that operated from 1933 until 2007, when the organization’s name was changed to International Premium Cigar and Pipe Retailers (IPCPR). The organization changed its name again in 2019 to the Premium Cigar Association (PCA), though pipes and pipe tobacco industries are still represented in its program. One aspect of the RTDA/IPCPR/PCA are its trade conventions, which connect pipe-makers with customers, vendors, and other pipe-maker.

[13] English idiom. To not know someone “from Adam” means to not know who they are or anything about them.

[14] Of Pipes Unlimited. This name may be spelled incorrectly. Mr Wood does not remember how to spell Ken’s surname, and admits that he could never remember to spell it at the time that they were working together. Corrections are welcomed.

[15] Association of Independent Tobacco specialists, a British trade organization that, like the American RTDA, operates conventions for industry personnel and clients.

[16] The “Chevin,” or “Otley Chevin” is a hilly area in Otley, a town in West Yorkshire, in the north of the UK.

[17] German pipe-maker and former joint-owner of Dan Pipe.

[18] Dan Pipe was a German pipes and tobaccos distributor and sister company to Dan Tobacco Manufacturing, one of the world’s largest tobacco manufacturers. Dan Pipe was L&JS Briars’ German distributor. Correction: the non-English speaking individual referenced here was initially identified as Dr Heiko Behrens. It has since been brought to our attention by a former business associate that Dr Behrens was fluent in English, meaning the unknown individual will have been someone else within Dan Pipe management.

[19] It appears that a “Ferndown” brand tobacco was imported into the US by James Norman Ltd. These blends are no longer in production and were presumably a Dan Tobacco product. “Elwood” is a tobacco brand owned and manufactured by Dan Tobacco. At present, Elwood Flake No. 2 is still being manufactured, however Elwood Blend No. 1 and Elwood Blend No. 3 are no longer in production.

[20] Ferndown, though Elwood, made several Pipe of the Year models for Dan Pipe.

[21] Holmer Knudsen is a German pipe-maker and frequent collaborator with Dan Pipe. For the Dan Pipe 2009 Pipe of the Year (also referred to as “Dan Pipe 2009”), Holger Frickert came up with the design (a short bulldog chambered for 9mm filters), Holmer Knudsen turned the bowls and cut the mouthpieces, and Les and Dolly Wood finished the pipes in their signature “Bark” rustication. Mr Wood also mounted sterling silver collars on the final product.

[22] The Sir John Cass School of Art was an art school in the East-End of London

[23] A set of technical qualifications administered by the City and Guilds of London Institute.

[24] A Distinction is the highest grade bracket awarded in City and Guilds courses.

[25] Duncan Briars was an English pipe company founded in 1899 by John Louis Duncan. Peter Wilson was a pipe-maker and manager at Duncan Briars.

[26] Jean Marie Alberto Paronelli (1914-2004) is considered one of the founders of modern Italian pipes.

[27] The most common rustication technique employs the use of a many-pronged hand tool, which allows the user to tear off chunks of briar to achieve a desired effect.

[28] After the Second World War, Dunhill began to manufacture table lighters decorated to look like fish swimming in a tank. These lighters have since become collector’s items worth thousands of dollars each.

[29] A British television show centred around antiques fairs. The show includes segments where members of the public bring their own antique items to be appraised by a professional in the industry.

[30] An English pipe-maker. Fromm began his career at English pipe company Invicta Briars before moving on to create his own Castleford make. Fromm was later hired as a production manager for Charatan after the company was acquired by Dunhill (the second time).

[31] An English pipe company established by George Walker, formerly of Duncan Briars, and his son Peter Walker, in 1958. Originally established as a pipe repair company, Ian Walker, son of Peter and grandson of George, began making pipes in the 1980s. Northern Briars continues to make and repair pipes under Ian’s stewardship.